These Rules Were Made for Breaking: an editor’s perspective on grammar

Lucy (Editor)

Prescriptive vs. Descriptive Grammar

When most people think of grammar, they think of an exact set of rules that must be followed for a sentence to be deemed ‘grammatically correct’. The kind of rules you’d learn from a textbook or in school. While true, this is just one approach to language referred to as ‘prescriptive grammar’. Prescriptive grammarians follow rules for how language should be used and how it should not be used, in everything from spelling to semantics, pronunciation and syntax with the aim of establishing ultimate language standardisation and correctness.

Descriptive grammarians, on the other hand, believe that language should be determined by how it is actually used, not how it should be used.

Writing and editing is very much a balancing act between these two approaches, and with that in mind, here are our favourite grammar rules that were very much made for breaking.

- You can’t start a sentence with a conjunction

Conjunctions are a small class of words used to connect other words, phrases and clauses, some examples of which include and, but, because, or and so. The word conjunction comes from the Latin coniunctio, meaning a union or joining together. As such, there’s no reason why conjunctions can’t also be used to join one completely different sentence with another.

Starting sentences with a conjunction is believed to make for fragmented writing. But at the end of the day, if it sounds natural, that’s probably because it is. Conjunctions at the start of a sentence can help build tension and suspense, increase pace and drive action forward, and add simplicity and poignancy. And they can emphasise a phrase that would otherwise be lost at the end of a sentence.

- You can’t end a sentence with a preposition

Eighteenth-century English bishop Robert Lowth wrote one of the most influential books on English grammar for prescriptive grammarians. As such, he is also to blame for many grammar myths.

Lowth claimed that prepositions (positioning words like at, by, for, into, off, on, out, over, to, under, up, with) shouldn’t go at the end of a sentence, but in doing so he used this exact construction himself: ‘This is an Idiom which our language is strongly inclined to.’

There are numerous examples where attempting to avoid placing a preposition at the end of a sentence results in language that is too formal or simply awkward to read. E.g. ‘James had no one with whom to play’ vs. ‘James had no one to play with’.

Always keep your audience in mind – reader experience is everything!

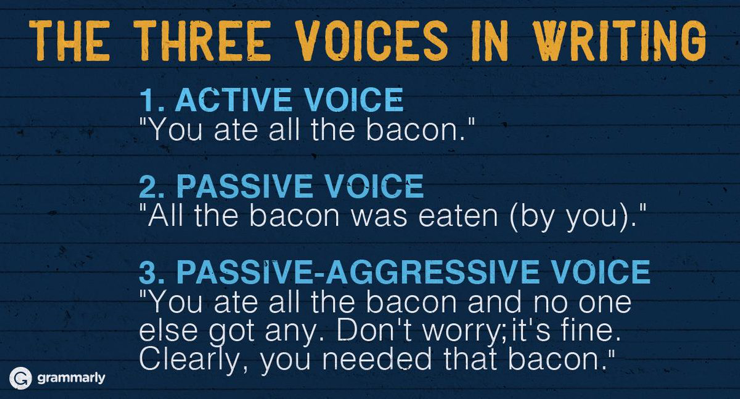

- You should avoid the passive voice

While it’s true that active sentences are clearer, punchier and lighter in general, all good writing requires balance. But like anything in life, moderation is key.

One example where the passive voice can shine is when the action is more important than the agent. For example, in the sentence ‘a candle was lit in honour of the dead’, the person who lit the candle is not as important as the image of the burning candle.

Another example is when the performer of an action is unknown, e.g. ‘mistakes were made’.

- You shouldn’t split infinitives

As lexicographer Robert Burchfield said of the split infinitive, ‘No other grammatical issue has so divided the nation.’ He also warned us not to ‘suffer undue remorse if a split infinitive is unavoidable for the natural and unambiguous completion of a sentence already begun.’ Don’t fret, we can’t all have the extensive vocabulary of Robert Burchfield.

The infinitive form of a verb is usually preceded by ‘to’, such as to learn or to love. Splitting an infinitive is simply placing an adverb between these two words: to quickly learn or to blindly love.

While it’s considered the safe option to avoid splitting infinitives, that doesn’t mean it’s the only option. Basically, if it sounds good, do it!

- Whose can’t refer to an inanimate object

Another rule we can thank Robert Lowth for, who wrote, ‘Whose is by some authors made the possessive case of which, and applied to things as well as persons; I think, improperly.’

Well, he thinks wrong. If you use whose to refer to inanimate objects, you’re in the company of Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Jane Austen and F. Scott Fitzgerald, to name a few. Yes, it can sound awkward and a lot of people don’t like it, but so far it’s the only word we’ve got. And using the alternative of which isn’t going to make you any more friends.

Consider: ‘The bus whose passengers were elderly went slowly around the bend’ vs. The bus, the passengers of which were elderly, went slowly around the bend’.

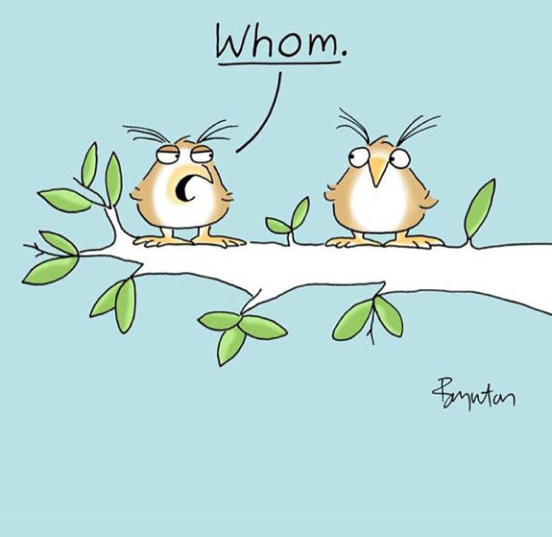

- You should always use whom when it’s correct to do so

While we can’t do away entirely with whom just yet, in conversation, informal writing and often fiction, especially for a younger or commercial audience, it is acceptable to use who in place of whom in some instances. For example, ‘Whom is the cake for?’ can become ‘Who’s the cake for?’ and ‘Whom should I talk to?’ can become ‘Who should I talk to?’

- Double negatives are ungrammatical

Although not ungrammatical (see what I did there?), double negatives are usually just confusing. However, there are cases where they can be used to inject greater meaning and expression into an otherwise ordinary sentence. For example, consider the sentence: ‘He looked so helpless, I couldn’t not go to him.’ The double negative here imparts a deeper, almost irrepressible need in the subject.

Another example is the double negative that means the opposite of what it says: ‘He wasn’t unattractive’ probably means he wasn’t exactly a looker either.

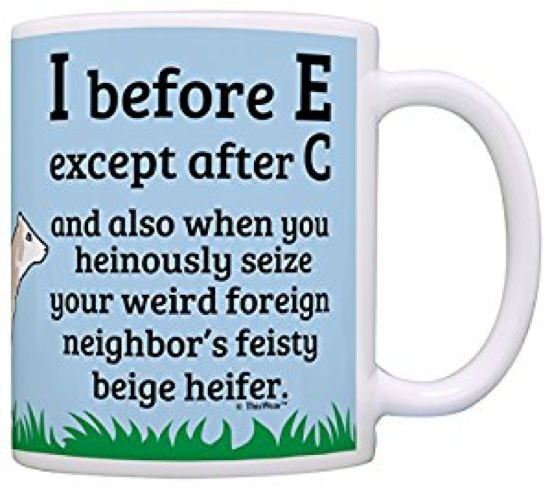

- I before E except after C.

To be a good writer, and a good editor, you need an understanding of both prescriptive and descriptive grammar, to know when to follow the rules and when the rules can be broken. To be able to follow a descriptive model of grammar, you must first have a solid understanding of prescriptive grammar. You have to know the rules to break them! And none of these exceptions to the rules are more important than when writing dialogue, the number one example of descriptive grammar.

I’ll leave you with this question: if a descriptive model of language is correct, why do we have prescriptive rules in the first place?